|

| |

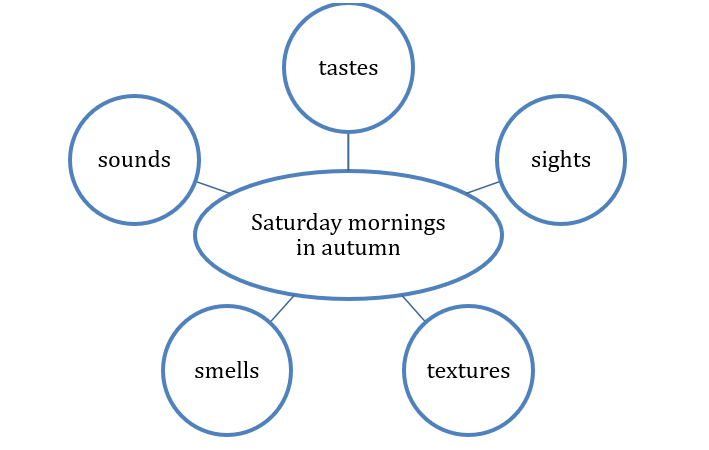

Creative Writing and Critical Thinking with Breath PoemsBy Patrick T. Randolph Introduction “Poetry is painting that speaks.” (Plutarch) What kind of poetry has a total of four lines (including the title) and is a mere 10 syllables long? What kind of poetry creates a spiritual and physiological experience for the performer? What kind of poetry gives even the student of electrical engineering goose bumps and inspires enthusiastic grins as she writes her verse with winks and whispers? The answer to these not-so-trivial questions can be summed up in two words—breath poems! The breath poem is a wonderfully economical kind of poetry that can be used for a myriad of purposes: for warm-ups or full lessons, as an opportunity to review syllables and stress, to enhance the art of being concise, to practice creative summarizing, to offer help in giving students a sense of control in their writing, to encourage confidence in English, and, most important, to simply play and have fun with words and their communicative powers. What is the Breath Poem? “A human being is only breath and shadows.” (Sophocles) The breath poem is a holistic experience of mind, body, heart, spirit, and soul. It is a style of poetry I created to see just how few syllables I could use and still tell a story in verse with a voice. Moreover, I wanted to help my students develop confidence in writing poetry without making the experience overly daunting. The structure of the breath poem includes a title (which is very important in that it frames the setting or background of the poem) and three lines: The first line contains three syllables as does the second line, and the third or last line contains four syllables, making it a total of 10 syllables. Reading the Breath Poem “To master our breath is to be in control of our bodies and minds.” (Thich Nhat Hanh) Another unique factor of the breath poem is the manner in which it is to be read. Breath poems ought to be read aloud, and it is this aspect which engages both the meditative mind and the dynamics of the body. After reading the title, the first three-syllable line is to be read while the reader inhales. The second line is to be read while the reader exhales. The third line is read while the reader both inhales and exhales. Here the reader can inhale the first syllable and exhale the last three or inhale the first three and exhale the fourth and final syllable. The breathing pattern is done so that the reader can get into the rhythmic state of the poem and feel the poem’s words and ideas by the “dance of the breath.” It may take a bit to feel comfortable with the breathing patterns, but before long it will be very natural and soothing for the reader. There is also the notion that in actually “breathing the poem,” the reader becomes the poem and will begin to feel the language on a whole new level. This “getting lost in the poem,” as it were, helps English language learners (ELLs) to paint a deeper image of the words in their minds by reading them, visualizing them, and breathing them. Benefits for the Learners “Poetry is nearer to vital truth than history.” (Plato) Despite the breath poem being so compact in nature, its benefits for ELLs are colossal in number and possibility. The first major benefit deals with vocabulary acquisition, and the benefit of this concept is echoed in recent neuroscience research on descriptive words and their relation to the brain. Studies have shown that descriptive and sensory-rich lexical terms stimulate the students’ brains at a higher level; consequently, these terms find their way into the students’ long-term memory with greater ease than dry, dull academic terms (Paul, 2012). In short, the words used in the breath poems enhance the ELLs’ vocabulary. Second, these short but powerful poems boost the students’ confidence level in terms of being able to both control their language and play with it at a deeper level (Randolph, 2011). Third, it helps students see how certain grammar patterns work and how certain grammatical markers, such as articles, are necessary in some cases and superfluous in others. Fourth, breath poems help students learn the difference between weak and strong vocabulary items and their cultural connotations. Fifth, students, in working with these poems, will discover the beauty and subtlety of alliteration and also how certain words best collocate with others to form artistically rich scenes or feelings. Sixth, students learn to summarize their thoughts and convey their images in a tight and concise fashion. There is perhaps no better practice for summarizing than poetry, and the breath poem takes this to an extreme with a limit of 10 syllables. And seventh, the breath poem helps students befriend English and enter into a closer linguistic relationship with the language. It helps them claim ownership to the language and foster what Guiora et al. (1972) called the language ego. Writing Breath Poems—The Procedure “Poetry is composing for the breath.” (poet Peter Davison) DAY 1: Setting the Stage Part I The introduction of this activity is as important as anything, so I always make it count. I have the students stand up, and then I ask them to go out into the hall. Together we run at a moderate pace up and down the hall and return to the classroom, where they take their seats. I ask the students, “What did you just do and what did it cause you to do now?” I point to my lungs and mouth to focus on the desired response. Usually they answer, “We ran and are now breathing hard!” Others might respond, “We are out of breath.” Of course, the key word I am looking for is “breath.” We, then, discuss (a) what the importance of the word “breath” is and (b) what the idea of breath represents for all living creatures. Part II Next, I go over the concept of English syllables. This will be a review for most levels, although these tricky creatures still pose difficulties for even the most advanced learners of English. I usually start the review by asking the students about objects around the room like “light,” “whiteboard,” “document camera,” or “window.” Then, I ask them to identify the number of syllables in their respective first names. This is always great fun, and it seems to help a good deal. The third stage is to have the students count the number of syllables in phrases such as “moonlight laughter,” “secret glance,” or “wild music.” Part III The last part of the first lesson is to use what I call a sensory play with words. I write a word, phrase, or idiom on the board such as “autumn” or “Saturday mornings in autumn” and then go through the senses as a way to discover the poetry of words. For example, “What smells come to mind when I say ‘Saturday mornings in autumn’?” or “What sounds do you hear when I say ‘Saturday mornings in autumn’?” I use the diagram below for this activity.  Figure 1. The sensory play with words. DAY 2: Painting Images with Breath Poems Part IV This second lesson focuses on explaining the structure and idea behind the breath poem and the actual writing of one to two poems in class. We go over the importance of the title, the number of lines, and the syllable count. I, then, give the phrase from the day before ("Saturday mornings in autumn"), and we review the sensory play with words. This activity is a nice lead-in to the students composing their first breath poem in class. It is best to write one together as a class, and then have the students pair up and write one on their own. With respect to the student-generated poems, I usually pick two or three and write them on the board to go over the syllable count and the examination of weak versus strong words. Before concluding, I should point out one very important element. The most crucial factor in writing these kinds of poems is to focus on getting the images down first, and then later attend to the syllable count. If the syllables become the focus, it will be too challenging and take the fun out of the whole experience. So, the initial focus should be on painting the images in the lines of the breath poem. After the images are created, then the carving away of syllables can take place, and this, in its own right, can be a great deal of fun (Randolph & Ruppert, 2020). The breath poem below is a clear example of first setting up the images and then carving away until the 3-3-4 syllable count remains. First Version Travelling Companion on Route 12 A summer turtle pulls his small shadow across the country road. Second Version Travelling Companion on Route 12 Turtle pulls his shadow across the road. Notice the trimming of unnecessary words from the first to the second version, and yet the essence of the first is not, in any way, changed in the final version. In fact, it is tighter, crisper, and really captures the essence of the moment on the road. Concluding Remarks “Every breath we take is a poem born for the first time.” (Patrick T. Randolph) For the inexperienced poet, teaching these 10-syllable creatures might seem rather daunting. But I suggest that every instructor bravely crawl out of his or her comfort zone, smile, take a deep breath, and jump into the wonderful world of miniature verse. As noted above, the benefits are numerous, and the uses are equally limitless for any ESL or EFL classroom. I, however, believe the best part of writing these is the confidence it creates in the students and the pride they take in trying to play with a language that quickly becomes more than a tool, for it actually becomes a friend to be cherished and respected with great awe. References Guiora, A. Z., Beit-Hallahmi, B., Brannon, R. C. L., Dull, C. Y., & Scovel, T. (1972). The effects of experimentally induced changes in ego states on pronunciation ability in a second language: An explanatory study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, (13) 5, 421-428. Paul, A.M. (2012, March 17). Your brain on fiction. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com Randolph, P.T. (2011). Using creative writing as a bridge to enhance academic writing. Selected Proceedings of the 2011 Michigan Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Conference, 1, 69-83. Randolph, P.T., & Ruppert, J.I. (2020). New ways in teaching with creative writing. Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press. Image from www.pixabay.com Patrick T. Randolph specializes in creative and academic writing, vocabulary acquisition, speech, debate, and mindfulness practices for both teachers and students. He has created a number of brain-based learning activities for the language skills that he teaches, and he continues to research current topics in neuroscience, especially studies related to exercise and learning, memory, mindfulness and meditation, and mirror neurons. He lives with his wife, Gamze; daughter, Aylene; cat, Master Gable; and puppy, Bubbles. Randolph has published two volumes of poetry: Father’s Philosophy and Empty Shoes—Poems on the Hungry and the Homeless. Proceeds from both collections go to benefit Feeding America and other American food-bank and homeless programs. Correspondence concerning this article can be addressed to patricktrandolph@yahoo.com | |

| Spring 2022 - Volume 50, Issue 1 |