|

| |

Get More Out of Your Listening/Speaking TextbookHeather Torrie, ITBE Link Editor  They say everyone has a book inside of them, waiting to be written. You could also say that everyone of us has an ITBE Link article inside, waiting to be written. I thought I would share some thought I have relating to my everyday teaching methodology. I hope to inspire each one of you to contribue to the Link this year. They say everyone has a book inside of them, waiting to be written. You could also say that everyone of us has an ITBE Link article inside, waiting to be written. I thought I would share some thought I have relating to my everyday teaching methodology. I hope to inspire each one of you to contribue to the Link this year.Introduction If you are a new ESL teacher, you might feel intimidated and cling to the textbook, doing each and every activity. If you are a more seasoned teacher, you may be tempted to disregard the textbook, instead supplementing with your favorite materials and self-created activities. Before you toss the book aside and flip on that exciting Youtube video clip, there may be more you can do with your basic listening/speaking textbook. Check your textbook for these elements: transcripts, vocabulary-building material, and audio files that can be downloaded or imported. These textbook elements can be used for much more than the published directions state. Transcripts Many listening textbooks today come with a transcript to the audio. Depending on the publisher, you will find it in various locations. Some books include the transcript as part of the teacher’s manual, while others include the transcript in the back of the student book. Wherever it is, you can make this available to your students and you can use it in many ways in your lesson. If there is no transcript available, you might want to consider creating your own, although it does take a bit of time. Transcripts can be used for many different purposes. Here are a few ideas: Vocabulary identification. After playing the audio passage for comprehension, you can play it an additional time and have students fill in the blank with vocabulary words they hear. This works best for a transcript in an online format, where you can easily copy/paste into Word and insert blank lines. Reading/listening fluency. I often play the passage once for students to identify the main idea, then a second time while they are reading the transcript. This can help increase both reading and listening fluency, especially with academic texts. Discourse markers. Lecture passages, especially those in ESL listening and note-taking textbooks, often are quite structured and use discourse markers such as “first of all,” “let’s move on to,” “in addition to…,” “for example,” etc. For these types of listening passages, I sometimes have my students read through sections of the transcript before listening and highlight signals and transition words that can help them understand the main parts of the lecture. They can underline cues on their paper and/or create a list to have in front of them while listening. If they can identify them on paper beforehand, they will be able to better identify them while listening. Suprasegmental pronunciation. When teaching sentence-level stress, as well as intonation, it is helpful for students to listen to speech samples and identify which words are stressed. Because the listening passage in the textbook unit is already familiar to the students, it can be a convenient source for this activity. For the sake of simplicity, I usually just use the beginning of the passage. I print out the first ten lines or so of the transcript and have students listen again to that part and mark which words are stressed. After they feel confident in the suprasegmental pronunciation, they can practice reading the transcript aloud in pairs (alternating parts if the material is a dialog, or alternating between sentences if a monologue).  Source: Q: Skills for Success 2 Listening and Speaking Most textbooks include a list of pertinent vocabulary words contained in the listening passage for the unit. These words are often presented with a context, such as a short reading or dialog. Some textbooks have audio recordings of the vocabulary-building text, which can be used for extra speaking practice.  Source: Pathways Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking 4 Read aloud. Even if you choose not to have students mark pronunciation aspects, like word stress, it can still be beneficial for students to simply read the dialog or passage aloud with a partner. They can listen to and coach each other with the pronunciation of less familiar words. Parsing/Editing of Audio Files If you can import the audio into a sound editor, such as Audacity, you can separate the passage into smaller pieces for various activities. Once students become familiar with the passage by doing the comprehension exercises, consider what else students can learn from the material. Shorter excerpts can be used for focused practice. Identification of verb tenses. It is important for learners not only to be able to produce speech using the proper verb tense, but to also recognize it while listening. Verb tense can make a big difference, especially if it is a simple past statement—meaning the action is complete and over—versus the present perfect, where something has relevance to the present. You can help students practice this type of recognition by parsing out short clips from your textbook audio that are in different tenses. For example, last semester I had my students students listen to the following audio (created by parsing out sentences and phrases from the textbook audio from the last two units we did):

As they listened to the exerpts, students mark the proper verb tense on a worksheet.

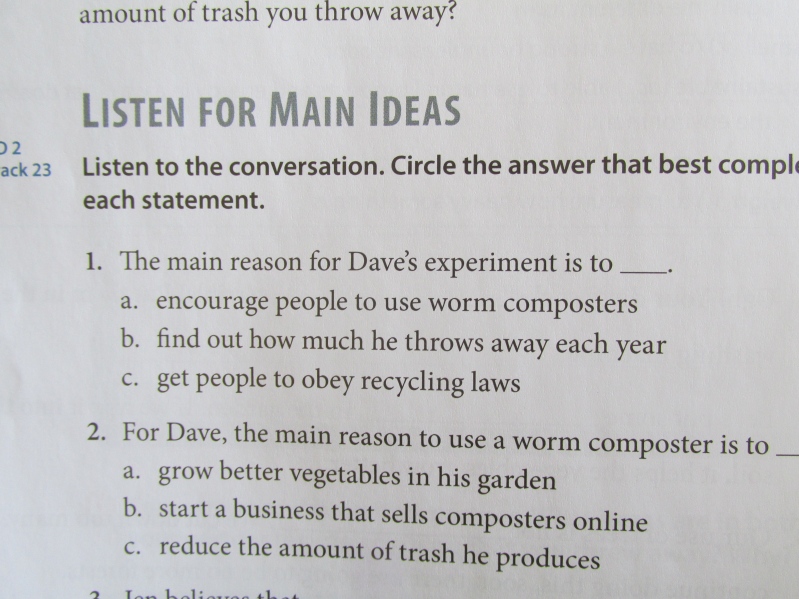

Follow-up questions. One of the objectives in our program is active listening skills. To help learners develop the ability to ask effective follow-up questions, you can parse out clips from the audio where the speaker is making some kind of statement or giving some information. Then, have the students create follow-up questions that could be asked. Inference questions. Sometimes, inferences about the text can be made based on short segments. For example, if the audio is an interview, sometimes it is difficult for students to answer an inference questions without bringing to their attention the exact segment they should focus on. By parsing out a short clip, you could play it and then ask the students to answer the question. Comprehension Questions Of course, comprehension questions are a given. But notice how the questions are presented. Don’t be afraid to modify these tasks to build and expand your students’ listening comprehension skills. Item format. Most likely, these items will be in the format of multiple-choice or true/false. If the main idea questions are written as multiple-choice items, rewrite them on the chalkboard or a handout without the answer options. Once students have their answers written, they can compare with the multiple-choice options given and see if their answer was close to any of the options. Consider the example below.  Source: Q: Skills for Success 2 Listening and Speaking These main ideas questions can be re-written on the chalkboard as:

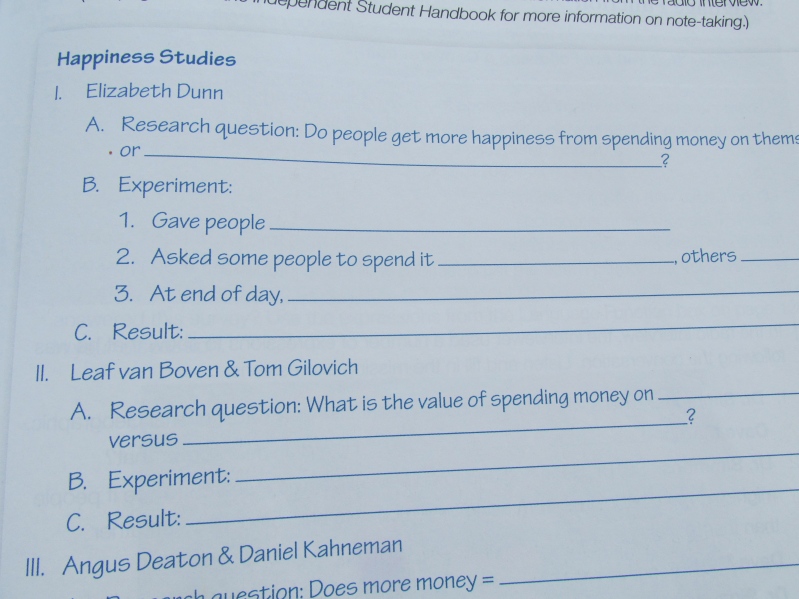

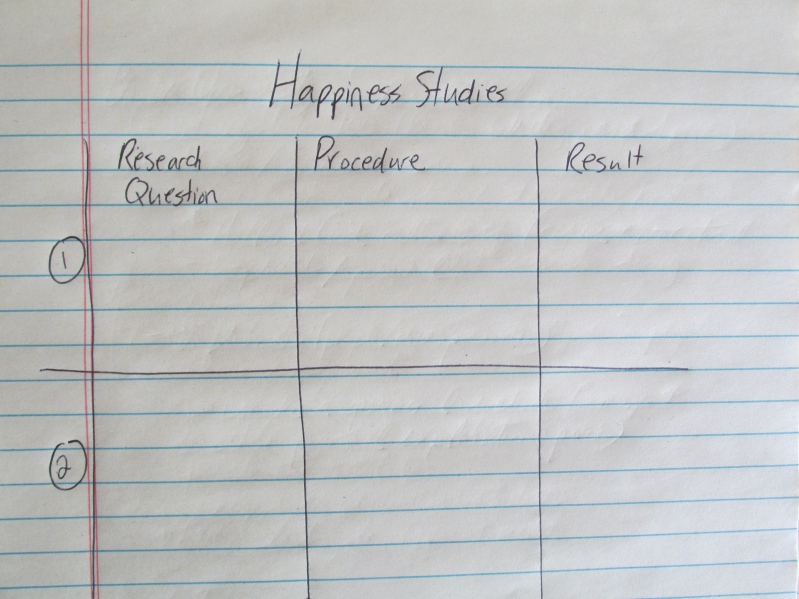

1.Why did Dave do the experiment? 2.Why did he use a worm composter? Have students close their books and focus their attention on the main ideas, rather than listening to hear the language in the item distracters. Afterward, they can discuss their answers and compare with the multiple-choice options in the book. Note-taking grids. Some textbooks include short note-taking activities where students can fill in the blanks in a partially completed outline. Sometimes, I don’t always like the way the outline is organized in the book. My advice is not to be afraid to have students close their book and create a better note-taking grid on the board or on a worksheet. This is a good way to effectively use the textbook material, but at the same time, get your students’ noses out of the book.  Source: Pathways Listening, Speaking, and Critical Thinking 4

You can have your students draw this simple chart in their notebook, an alternative to the sentence-completion style in the text.  Conclusion As ESL teachers, we often suffer from burnout due to “reinventing the wheel.” We can increase our efficiency, as well as our effectiveness, in teaching as we learn to work smarter and maximize the resources that we have right at our finger tips…like that textbook sitting there on the desk. Heather Torrie is the Testing Coordinator in the English Language Program at Purdue University Calumet. She has been the editor of the ITBE Link since July 2013. References Brooks, M. (2011). Q: Skills for Success 2 Listening & Speaking. Oxford University Press. MacIntyre, P. (2013). Pathways Listening Speaking, and Critical Thinking 4. National Geographic Learning/Cengage. | |

| ITBE Link - Winter 2015 - Volume 42 Number 4 |