|

| |

The Magic of Movement: Exercise's Phenomenal Impact on the Language Learner's Brain

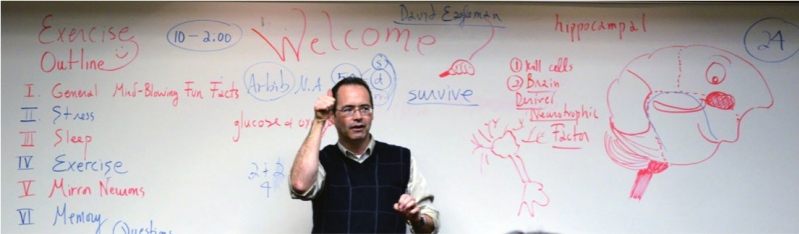

Patrick T. Randolph. Faculty Language Specialist, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo This article is the second in a multi-article series based on “What Every Teacher Needs to Know About the Brain,” a presentation given at the 2013 ITBE Convention in Lisle, IL. Introduction“Walking is the best possible exercise.”

—Thomas Jefferson What happens to you after returning from an invigorating run or a well-deserved walk? Is your smile a bit bigger perhaps? Does your mood change from fine to fantastic? Is your soul lighter and happier? Do you feel somehow reborn and more grateful for the simple things in life? Are your senses heightened and is your mind clearer? Has the stress you had before the walk or run magically disappeared? Chances are, you have answered “yes” to most of these questions. Exercise really is the key ingredient for mental and physical health, that crucial element Hippocrates believed in over 1,600 years ago: “If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the safest way to health” (Hippocrates, 1931 version). The Problem“Only ideas won by walking have any value.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche John Medina, a developmental molecular biologist, refers to exercise as “cognitive candy” (2009, p.22); Antronette Yancey, a physician scientist, claims physical activity “improves children” (Medina, 2009, p.18); John J. Ratey, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, argues that exercise “makes the brain function at its best” and he asserts that “the point of exercise is to build and condition the brain” (2010, p.3). Yet with almost weekly reports being published on exercise’s benefits for the brain, exercise and physical education programs remain nonexistent in most, if not all, higher education ESL programs. In this sense, ESL students who are still in K-12 are extremely fortunate, for they are usually able to participate in their schools’ physical education classes. The problem rests in higher education: Why don’t our ESL institutes across the country provide exercise classes for their students? Moreover, there is the general problem that spans across our entire educational system: the fact that in almost all of our classes, the students are sitting down! Why are they not standing and moving around more in the classroom? Remember, we evolved as a moving, walking species—not while sitting down glued to a computer screen! “Learning and memory evolved in concert with the motor functions that allowed our ancestors to track down food, so as far as our brains are concerned, if we’re not moving, there’s no real need to learn anything” (Ratey, 2010, p.53). Exercise and movement are crucial for learning and memory (Medina, 2009; Jensen, 2008; Ratey, 2010; Sousa, 2011), so in order to create better brains, to improve classroom environments, and enhance education, we need to facilitate as much movement in the class as possible without disrupting the learning process. But how is such an atmosphere created? What can be done to get the students moving? Before answering these questions, let’s review why exercise is so vitally important and show the benefits of movement and activity. The Benefits for the Brain“To improve your thinking skills, move.”

—John Medina A recent 13-year study showed that for every minute you walk, you add one and a half to two minutes to your life (Cool, 2012). If just walking can do that for your longevity and health, then just imagine what it can do for your brain! One of the most significant impacts of exercise on the brain is its influence in optimizing the readiness for the brain to process new information by being alert, focused, and motivated (Ratey, 2010). Exercise is one of the best ways to regulate the production and release of neurotransmitters—these are crucial chemicals for learning and memory. These wonderfully potent chemicals help regulate our responses to pain and pleasure, our emotional states, and our cognitive performances. They are what keep our emotional and physical processes in balance. Let’s review five particularly important ones that have a large role in maintaining a proper balance for effective learning. Five Neurotransmitters of Great ConsequenceAcetylcholine: This was the first officially identified neurotransmitter; it was discovered in 1914, almost a century ago. Acetylcholine has a colossal role in our ability to learn, for it is involved in attention, arousal, and memory. The more we exercise, the more we facilitate its production and regulation of these systems.

Dopamine: Dopamine can be increased by a healthy diet, sufficient sleep, and exercise. Dopamine is best known as the neurotransmitter responsible for controlling the reward and pleasure centers of the brain. It is dopamine that keeps us engaged in the rewards of learning and helps us seek those rewards out. Dopamine also affects the neural processes that deal with mood, emotional responses, movement, learning, and attention. In addition, according to Knecht et al., dopamine plays a significant role in our working memory (2004). Epinephrine (also called adrenaline): Low levels of this neurotransmitter cause us to be tired, have difficulties in losing weight, and also make it hard to focus. As the name implies, epinephrine is produced from norepinephrine, so exercise’s production of norepinephrine is doubly significant. Epinephrine itself is responsible for regulating our attention and arousal systems (Ratey, 2010). How well our students focus mentally and use their cognitive skills depends on their levels of epinephrine. Moreover, epinephrine is paramount in increasing the amounts of oxygen and glucose – the two crucial ingredients for a happy, healthy, and efficiently functioning brain. Norepinephrine (also called nonadrenaline): Exercise helps increase the amount of norepinephrine (Medina, 2009). This neurotransmitter has a substantial effect on many areas of the brain; for example, it affects the amygdala (a home for emotional responses and memory), the hippocampus (another important memory and learning center), and the cingulate gyrus (significant in coordinating sensory input with our emotions). The three aforementioned areas are pivotal players in the learning and memory process (Sousa, 2011). Norepinephrine is also vital as it helps facilitate the release of glucose—as above—one of the brain’s most beloved sources of energy! In addition, norepinephrine heightens our arousal, reward, and attention systems—these are also important for bringing the brain to its optimal level in the classroom. Serotonin: Like dopamine, serotonin can be increased by a healthy diet and moderate exercise. Exposure to sunlight is also a way to increase our levels of serotonin (Young, 2007). Serotonin improves our moods, regulates how we learn, sleep, and deal with anxiety, and, equally important, it helps regulate our appetites; it is therefore often thought of as the “happy neurotransmitter.” Moreover, it aids in keeping our general brain activity under control (Ratey, 2010). Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor — “Miracle-Gro for the Brain”Not only does exercise help regulate the wonderful world of neurotransmitters, but it also helps produce one of the most important and potent neurotrophins that there is — brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Jensen, 2011; Medina, 2009; Ratey, 2010; Reynolds, 2012). A neurotrophin is a “factor” or “substance” that actually strengthens neural communication and builds up our neural circuitry. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is so powerful that Ratey has termed it “Miracle-Gro for the brain” (2010, p.40). What BDNF does that is so amazing is that it helps create neurogenesis—the production of new baby neurons in the hippocampus—that great center for memory and learning. In addition, BDNF helps strengthen the connections and communication among existing neurons (Reynolds, 2012; Ratey, 2010), creating a great opportunity for learning and memory to literally blossom and grow with great speed.

“I Exercise, Therefore I am” — What Descartes Should Have SaidWhat René Descartes should have said was, “I exercise, therefore I am.” For it is undeniable that exercise aids in learning, memory, attention, reasoning, and a whole host of other cognitive functions. It helps regulate the workings of neurotransmitters and the production of BDNF, it increases oxygen and glucose, and makes us feel fantastic and refreshed. “Given all the activations happening at once, physical performance probably uses 100 percent of the brain” (Jensen, 2011, p. 39).

Students who exercise before class also seem to improve their rate of learning (Ratey, 2010). We know that exercise increases the oxygen in the blood—one of the brain’s preferred sources of energy. “Studies confirm that higher concentration of oxygen in the blood significantly enhance cognitive performance in healthy young adults” (Sousa, 2011, p.238). But young adults are not the only ones who benefit—all ages can benefit from exercise. A 2007 study in Germany found that adults “learn vocabulary words 20 percent faster following exercise than they did before exercise…” (Ratey, 2010, p.45). The study focused on 27 healthy subjects and looked at learning outcomes after one week and again after eight months. It was no surprise that an increase in BDNF levels accompanied this increased speed in vocabulary acquisition (Winter et al., 2007). Exercise in the Classroom“Getting out and moving around is key.”

—Eric Jensen How, then, can we get our students up and moving before and during class? What can we do to help create new neurons, maintain the old ones, and strengthen the current neural connections? How can we facilitate learning and enhance their memory? The answers are actually limitless and depend on the creativity of each instructor. I, however, will offer a few physical activities that I use on a daily basis. These make the class fun, keep the students focused, help them learn, and surprisingly inspire and motivate them to exercise more on their own. In Class Exercises: One very simple and effective way to increase an oxygen supply to the brain and improve its performance is to do stretching and minimal exercises at the beginning of class, then repeat these exercises every so often to keep the students fresh, alert, and focused. An example of an easy, fun, and full-body exercise routine is provided in the following Youtube video: Patrick T. Randolph’s Exercise for the Brain (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E65StVJTzVU). Exercise Stations: In Brain Rules, Medina offers the suggestion of having students walk on treadmills during class (2009). Although this is a fantastic idea, it is unrealistic in terms of space and cost. A less expensive version of Medina’s idea is to designate a corner of the classroom as the “Exercise Station.” In this corner of the room, the student or students in need of an oxygen boost, can do stretches, quietly run or walk in place, do knee bends, or any other physical exercise that offers a healthy dose of oxygen and glucose to the brain. No Running in the Hall? While running in the hall might be a little extreme or even against certain campus rules, there is no law against having your students walk briskly in the halls. Before class starts or in the middle of class, it is a great idea to get your students out and walking at a healthy clip for a few minutes. Studies at the Harvard Medical School and at the Franklin Institute claim that the simple act of walking increases the needed amounts of oxygen and glucose for the brain. “Walking provides a more effective means of oxygenating your brain than strenuous exercise” (Adams, 2011). The reason for this is fairly logical; strenuous types of exercise push your muscles to function at a higher level, therefore requiring them to use more oxygen and glucose. This, of course, leaves less amounts of fuel for the brain (Adams, 2011).

Clap — The Music of Success: Another very simple yet energy-full activity is getting the students to clap for their classmates when one gives an impressive, correct, or creative answer to a question. The act of clapping also gets the blood moving, and the excitement naturally stimulates the brain. In addition to the movement, the whole idea of praising and being praised elicits a healthy flow of neurotransmitters that will help in motivating the brain to learn.

Stand & Deliver: Having your students stand up to answer a question or even ask a question may seem old school, but if you’ve ever watched the British politicians debate, they stand and deliver an argument then sit down and do it all over again with great energy and enthusiasm. These debates, in fact, are livelier than most professional soccer matches! It keeps the politicians sharp, focused, alert, and ready to solve problems on the spot. If our classrooms could mimic this, just think of all the learning that could take place. So give this a try, it really works and keeps the students engaged in the lesson.

Researching Exercise — Internalizing the Benefits“Your life changes when you have a working knowledge of the brain.”

—John Ratey

Doing actual exercises keeps our students’ cognitive functioning at good, healthy, and productive levels. The more they stay active, the better they will perform. But what about academic activities that will reinforce the old Greek proverb—A sound mind in a sound body? How can we get our students to become intellectually involved with learning about exercise’s impact on the brain? Here are four classroom activities that answer this question and promote awareness of exercise and mental health. Readings, Discussions & ResponsesThere are literally countless articles written every week on the positive effects of exercise on the brain. But three very solid, readable, and reliable sources are chapter one of John Medina’s Brain Rules; chapters one and two of John J. Ratey’s SPARK! How exercise will improve the performance of your brain; and a number of the articles from the New York Times journalist, Gretchen Reynolds. Some articles of particular interest are “Getting a brain boost through exercise,” “Exercise and the ever-smarter human brain,” “Do the brain benefits of exercise last?,” “Laughter as a form of exercise,” and “How exercise benefits the brain.”One common way to get students interested in this topic is to simply have them do readings on exercise followed by class discussions. After the discussions, they can write up a summary of the discussion and a response as it relates directly to their personal lives. Interview I — Summary & ResponseFirst, help your students create a list of questions such as the following:(1) Do you think Americans like to exercise? Why? (2) Do you like to exercise? (3) Do you think it is good for you? Why? (4) Do you think exercise improves the brain’s performance? (5) Have you researched much about exercise’s effect on the brain? (6) Do you study better after a moderate workout? Next, have your students interview three or four domestic students on campus and collect the results. Discuss their results in class. Then, have the students write up a summary of their findings and a personal response to their data. Interview II — Reading Comparison ProjectA variation of the above is to have the students formulate a research question; for example, “Is walking the best physical activity for the brain?” Next, ask three to four domestic students this question and record their answers. Then, go online and find two to three sources that supply the answer to the research question. Do the interview results match the research? Finally, have the students either write up a summary of their comparison between the research and interviews or give a presentation on the results.Ethnography ProjectsThese types of projects are great ways to get the students out into their local communities to investigate why Americans do what they do (McPherron & Randolph, 2013). First, have the students observe Americans specifically doing some kind of physical activity: walking, bicycling, running, running with a dog, stretching, etc. Second, have them create hypotheses based on their observations. Next, help them create a list of questions so that they can interview three to five people who participate in the observed exercise. Have them record the responses and analyze the data. The final project for the lesson can either be an oral presentation or a written paper. For more details on this, see McPherron and Randolph’s article in the TESOL Journal, volume 4, issue 2.Concluding RemarksWithout doubt, exercise is the key to both physical health and academic success. To help our students reach their goals and have fun in the process, I’ve suggested we should get them up and moving in class; and, to reinforce this, I encourage you to have them do actual research on exercise and its wonderful effects on the brain. Ratey was correct when he said “Your life changes when you have a working knowledge of the brain” (2010, p.6). In fact, it will change even more when you know how you can improve the quality of your brain with the magic of movement and its impact on our great and grand universe of grey matter.Correspondence concerning this article can be addressed to patrick.randolph@wmich.edu. Patrick T. Randolph currently teaches at Western Michigan University where he specializes in creative and academic writing, speech and debate. He has created a number of brain-based learning activities for the language skills that he teaches, and he continues to research current topics in neuroscience, especially studies related to exercise and learning, memory and mirror neurons. Randolph has also been involved as a volunteer with brain imaging experiments at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He lives with his wife, Gamze; daughter, Aylene; and cat, Gable, in Kalamazoo, MI. References:Adams, G. (2011, January 20). How to increase oxygen to your brain with exercise. Livestrong.com. Retrieved from http://www.livestrong.com.Cool, L.C. (2012, September 11). The easiest way to live longer. Yahoo! Health. Retrieved from http://health.yahoo.net. Hippocrates, (1931). In Regimen, trans. by W.H.S. Jones. Vol. 4, 229. Jensen, E. (2008). Brain-based learning: The new paradigm of teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Knecht, S. et al. (2004). Levodopa: Faster and better word learning in normal humans. Annals of Neurology, 56, 20-26. McPherron, P. & Randolph, P.T. (2013). Thinking like researchers: An ESL project that investigates local communities. TESOL Journal, 4, 312-331. Medina, J. (2009). Brain rules. Seattle, WA: Pear Press. Ratey, John J. & Hagerman, E. (2010) Spark! How exercise will improve the performance of your brain. London: Quercus. Reynolds, G. (2011, November 30). How exercise benefits the brain. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://well.blogs.nytimes.com Sousa, D.A. (2011). How the brain learns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, A Sage Company. Winter, B. et al., (2007). High impact on running improves learning. Neurobiology of learning and memory, 87, 597-609. Young, S.N. (2007). How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 36, 396-399. | |

| The ITBE Link - Summer 2013 |