|

| |

“Lab Rats” at Work: Partnering with School-based Literacy Centers to Enhance the Performance of English Language LearnersDr. Anna Kuroczycka Schultes, Township High School District 214

Introduction As an instructional coach for English Language Learners in a large suburban school district, I spend the greater part of my day helping teachers implement effective pedagogical practices for students whose first language is not English.

Because these students do not have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) as special education students do, some teachers may not even know that they have exited ELLs in their classrooms. My goal, therefore, is to work with teachers, Professional Learning Communities within each building, and administrative teams to build the cognitive capacity for them to lead successful programs.

But what does success mean in the context of ELL instruction? How do we measure it? In a high school ELL classroom, success is especially difficult to quantify since any given class may consist of a variety of learners: new immigrants, students who have been in the country for several years but have not yet mastered academic language, long-term learners[1], or a mix of both mainstream and Limited English Proficient Students (LEP). Due to the diversity present when working with immigrant students, achievements are truly a result of the idiomatic “village’: ELL teachers, counselors, coordinators, and coaches, among others. For that reason, comprehensive high schools should strive to extend instructional opportunities beyond the confines of the classroom in order to build an accomplished program for English language learners. Background In thinking about external means of ELL support, i.e. apart from the instruction of the classroom teacher, I asked myself two guiding questions: “What outside-of-the classroom resources do teachers use to aide in ELL instruction?” and “What makes them successful?” I then directed these questions specifically to ELL and LEP teachers at two of the buildings in the district that house innovative literacy centers, referred to as Literacy Labs. It has been my observation that the Literacy Lab has been an effective intervention due to its popularity among staff and students. Of all the resources at teachers’ disposal, e.g. after-school tutoring, Rent-a-Tutors (affectionately referred to as “Lab Rats”)[2], Saturday School, instructional coaching, ELL coordinators and instructional assistants, 70% of staff responded that they prefer to use the Literacy Lab above all other supplemental resources. Not Your Typical Tutoring Center One of the reasons for such popularity of the Literacy Lab among teachers can be the multi-level collaboration that it offers:

-oral presentation practice -extra help

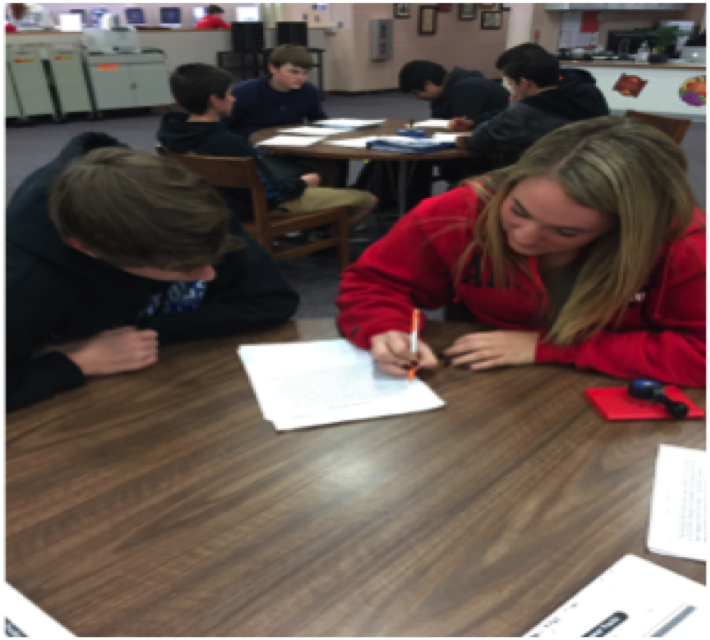

-reading comprehension -work completion -grammar -test corrections Due to the Literacy Lab’s increasing popularity among ELL science teachers at one of the two buildings, their Lab was also staffed with a science teacher in addition to the Language Arts and Social Science teacher who had already been working there the year prior.[3] More than half of the ELL teachers surveyed at these two buildings replied that they take their classes to the Literacy Lab on a regular basis, with 35% of teachers reporting that they go once or twice a quarter while 20% of respondents said they go once or twice a month. Therefore, some teachers may be frequenting the Literacy Lab potentially ten or more times per school year. Furthermore, 55% of respondents also have tutors come to their classrooms, which can be a very fruitful intervention as it gives teachers the opportunity to individualize instruction and check for understanding. ELL Tutor Training: Building Peer Relationships  The student-student level of collaboration can be used as a particularly powerful tool in the instruction of English Language Learners. Research in ELL instruction confirms the role of friends in immigrant students adjusting and committing to the learning process (Zimmerman-Orozco, 2015). Considering the popularity of the Literacy Lab & Rent-a-Tutors among ELL teachers, the administrative teams at both schools decided that the tutors, who are mainly upperclassmen (Juniors and Seniors),[4] should be armed with some basic strategies to work with ELL students. In observing the tutors working around the building, it was clear to me too that they needed this help. Many tutors would simply stand and wait for students to approach them instead of offering assistance or would explain a concept and walk away without checking for comprehension. As a result, I developed and conducted a training with all tutors, circa 200 in one building and 120 in the other, which aimed at providing them with basic tips for working with second language learners. The student-student level of collaboration can be used as a particularly powerful tool in the instruction of English Language Learners. Research in ELL instruction confirms the role of friends in immigrant students adjusting and committing to the learning process (Zimmerman-Orozco, 2015). Considering the popularity of the Literacy Lab & Rent-a-Tutors among ELL teachers, the administrative teams at both schools decided that the tutors, who are mainly upperclassmen (Juniors and Seniors),[4] should be armed with some basic strategies to work with ELL students. In observing the tutors working around the building, it was clear to me too that they needed this help. Many tutors would simply stand and wait for students to approach them instead of offering assistance or would explain a concept and walk away without checking for comprehension. As a result, I developed and conducted a training with all tutors, circa 200 in one building and 120 in the other, which aimed at providing them with basic tips for working with second language learners.Prior to the training, ninety-six tutors were surveyed in order to determine what they struggled with most in their experiences working with ELL/LEP students. Tutors at both schools responded in overwhelming majority that their greatest challenge was explaining difficult terms and concepts. The I.C.E. Training Model

I tell tutors to ask students to show them what they are working on and what they have completed thus far instead of simply asking, "Are you ok?" or “Do you understand?”, which will elicit a “yes” or “no” answer. Tutors can read a section of their writing and suggest improvement even if they were not asked a direct question. Oftentimes, ELL students may just be hesitant to ask. I also instruct tutors not to get too caught up in all of the mistakes an ELL student has made, and to utilize the “sandwich” method of starting and ending with a positive comment instead, i.e. “I love your first piece of evidence. It supports your claim very well. The commentary, however, doesn’t explain how it connects to the claim. Why don’t you use a stem? That will definitely make the sentence flow smoothly!”

If proof-reading, students should also focus on one particular aspect of the assignment: pointing out every single grammar error will overwhelm one’s tutee.Be Culturally Responsive In order to activate an ELL tutee’s background knowledge, I ask tutors to start by providing examples that are relevant to their experiences in order to help ELLs make links between past learning and new concepts. This can be a particularly powerful way for Literacy Lab tutors to connect and bond peer-to-peer in a way that ELL teachers potentially cannot since the tutors are more attune to the day-to-day lives of teenagers simply due to their age. I also underscore the need for tutors to show respect for cultural and linguistic diversity, which includes being sensitive to the cognitive demands of linguistic immersion. When I survey the Literacy Lab tutors about their preparedness to tutor language learners before our training, I inevitably receive a few responses in which tutors state that they do not believe that learning English as a second language for an immigrant is any different from English-only students attending their Spanish, French, or German class during the school day. What these tutors fail to understand, however, is the psychological component of language learning and how tremendously taxing of a process it is to have to navigate one’s entire day in a constant state of being at a “loss for words.” Be Efficacious / Effective Lastly, I emphasize to student tutors the necessity of being aware of their own language use in order to be more effective pedagogues; this includes not using idiomatic expressions which do not translate and can thus quickly and easily confuse ELL students. Oftentimes tutors may not be able to gauge whether an ELL student understood their directions or not. One way of doing so is by paying attention to an ELL’s body language. I suggest that tutors reword their question and see if it elicits a similar answer or attempt to use a graphic organizer, illustration, or photo. In addition, they should not be afraid to seek someone who speaks the native language of the tutee if they have exhausted their toolbox or strategies. Benefits of the Literacy Lab: ELL Students & Beyond “ESL students are my favorite demographic to tutor. They are so receptive to the tutoring and I love to hear their individual stories.” - Student Tutor

The benefits of partnering with school-based literacy centers, such as the Literacy Lab model outlined in this article are multifold. To start, for the ELL student (and very often for the more introverted tutors!), a tutoring session builds interpersonal skills and forces students to practice their oral communication. While tutees build their skill capacity, they also learn how to interact with their peers and advocate for themselves. Moreover, literacy centers create a sense of community and teach students the importance of collaboration and problem solving in a safe environment, which is immensely important for ELLs who can often be very dependent on others while learning how to navigate the American school system. The benefits of partnering with school-based literacy centers, such as the Literacy Lab model outlined in this article are multifold. To start, for the ELL student (and very often for the more introverted tutors!), a tutoring session builds interpersonal skills and forces students to practice their oral communication. While tutees build their skill capacity, they also learn how to interact with their peers and advocate for themselves. Moreover, literacy centers create a sense of community and teach students the importance of collaboration and problem solving in a safe environment, which is immensely important for ELLs who can often be very dependent on others while learning how to navigate the American school system.Dr. Anna Kuroczycka Schultes in an instructional coach in the Immigrant Education Program at Township High School District 214 in Arlington Heights, IL and is currently editing a book on immigrants and refugees. References Zimmerman-Orozco, S. (2015). Border Kids in the Home of the Brave. Educational Leadership, 48-53. [1] I use this term to identify ELL students who were either born in the United States or came here at a very young age, but who do not exit the ELL program prior to going to high school.

[2] This is an intervention coordinated by the Literacy Lab. Rent-a-Tutors are students who also tutor in the Literacy Lab.

[3] All three teachers are partially released from their teaching duties to work in the Literacy Lab for a total of 1.4 FTE.

[4] Students receive a service-learning credit for working in the Literacy Lab during what would otherwise be a lunch or study hall period.

| |

| ITBE Link - Spring 2015 - Volume 43 Number 1 |